If you have ever struggled with weight gain despite trying every diet and exercise routine, you might be surprised to learn that the answer lies not just in your lifestyle choices but deep within your gut.

Our digestive system is home to trillions of microorganisms that play a critical role in maintaining our health, including how our body processes food and stores fat.

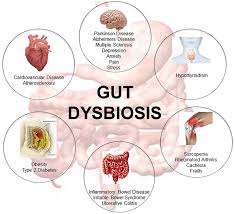

When the balance of these microorganisms gets disrupted—known as gut dysbiosis—it can lead to various health problems, including obesity.

In this article, leanandfit.info will dive into the fascinating connection between gut dysbiosis and obesity, exploring how the imbalance of bacteria in your gut may be making it harder to shed those extra pounds.

Contents of this Article:

- What is Gut Dysbiosis?

- The Role of Gut Microbes in Digestion and Metabolism

- How Gut Dysbiosis Alters Metabolism and Leads to Weight Gain

- Gut Dysbiosis and Inflammation: A Pathway to Obesity

- The Impact of Gut Dysbiosis on Appetite Regulation

- FAQs on Gut Dysbiosis and Obesity

- Examples from Daily Life: How Diet and Lifestyle Contribute to Gut Dysbiosis

- Conclusion: How Does Gut Dysbiosis Cause Obesity?

What is Gut Dysbiosis?

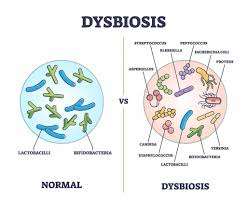

Gut dysbiosis is a condition where the balance of bacteria and other microorganisms in your gut is disrupted, leading to an overgrowth of harmful bacteria and a reduction in beneficial ones.

This imbalance can affect the way your body processes nutrients, responds to insulin, and stores fat, which plays a significant role in the development of obesity.

Our gut contains a vast microbial community, commonly referred to as the gut microbiome, which is crucial for maintaining a healthy digestive system.

In a state of gut flora dysbiosis, these microbes fall out of harmony, which can lead to a variety of health issues, including inflammation, insulin resistance, and, ultimately, weight gain.

The Role of Gut Microbes in Digestion and Metabolism

The microorganisms in your gut do more than just help break down food—they play a critical role in metabolism, nutrient absorption, and energy regulation.

Certain bacteria in the gut produce short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), such as butyrate, propionate, and acetate, which are important for maintaining gut health and regulating body fat.

However, when there is an imbalance of bacteria—like in intestinal dysbiosis—this production of SCFAs is disrupted.

Harmful bacteria begin to overpopulate, and beneficial bacteria that aid in digestion and metabolism are reduced.

This shift can directly affect how the body processes calories and stores fat, contributing to weight gain and obesity.

How Gut Dysbiosis Alters Metabolism and Leads to Weight Gain?

One of the key ways gastrointestinal dysbiosis contributes to obesity is by altering the body’s metabolism.

A healthy gut microbiome helps regulate how efficiently our bodies convert food into energy.

But when this balance is disrupted, it can lead to metabolic changes that favor fat storage rather than fat burning.

Studies have shown that individuals with gi dysbiosis tend to extract more calories from the same amount of food than those with a healthy gut microbiome.

In a study published in Nature, researchers found that transferring gut bacteria from obese mice to lean mice caused the lean mice to gain weight, even without changing their diet.

This research suggests that an unhealthy balance of gut bacteria can directly influence how much fat our bodies store.

Moreover, microbiome dysbiosis can lead to insulin resistance, which is a key factor in weight gain.

When your body becomes resistant to insulin, it struggles to regulate blood sugar levels properly, causing excess glucose to be stored as fat.

Gut Dysbiosis and Inflammation: A Pathway to Obesity

Gut dysbiosis, an imbalance in the intestinal microbiota, has been closely linked to obesity through various mechanisms, particularly chronic low-grade inflammation.

Here is how this connection unfolds:

1. Increased Gut Permeability:

An imbalanced gut microbiome can weaken the intestinal barrier, leading to a condition known as “leaky gut.” This allows harmful bacterial endotoxins, such as lipopolysaccharides (LPS), to enter the bloodstream, triggering widespread inflammation. According to Frontiers in Immunology, increased gut permeability is a key driver of chronic metabolic inflammation, which plays a role in obesity.

2. Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) Activation:

Elevated LPS levels in the blood activate immune responses, leading to persistent inflammation. This inflammatory state is a hallmark of metabolic disorders and contributes to insulin resistance. A study published in Physiology explains that higher LPS levels correlate with increased fat accumulation and reduced insulin sensitivity.

3. Altered Gut Microbiota Composition

Obese individuals tend to have a distinct gut microbiota profile, characterized by a higher ratio of Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes. Research from the National Library of Medicine suggests that this imbalance is linked to increased energy extraction from food, leading to greater fat storage. So, your gut bacteria influence your body fat percentage and most people are simply unaware of this phenomenon.

4. Short-Chain Fatty Acids (SCFAs) Imbalance:

Gut bacteria produce SCFAs, which help regulate energy metabolism and appetite. Disruptions in SCFA production can contribute to metabolic imbalances that promote weight gain. A study in Nutrients highlights how gut dysbiosis may alter SCFA levels, negatively impacting metabolism.

5. Disruption of Bile Acid Metabolism:

The gut microbiome plays a role in bile acid metabolism, which affects fat digestion and energy balance. A study published in Frontiers in Nutrition states that dysbiosis alters bile acid profiles, impairing lipid metabolism and increasing obesity risk.

Addressing gut dysbiosis through dietary changes, probiotics, and lifestyle modifications may help reduce inflammation and support weight management efforts.

The Impact of Gut Dysbiosis on Appetite Regulation

One of the most fascinating—and often underestimated—ways gut dysbiosis contributes to obesity is by hijacking the body’s appetite regulation system.

Our gut is not just a food processor; it is a full-fledged communication hub wired directly to the brain through the gut-brain axis. This bidirectional network uses nerves, hormones, and microbial metabolites to regulate hunger and satiety.

In a healthy gut, beneficial microbes help maintain a fine-tuned balance of appetite hormones. They produce short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) like butyrate and propionate, which signal the brain to reduce hunger.

They also support the secretion of satiety hormones like peptide YY (PYY) and glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1), both of which help you feel full after eating.

But when gut dysbiosis occurs—meaning the overgrowth of harmful bacteria and loss of beneficial ones—this communication system breaks down.

Research published in journals like Nature Reviews Endocrinology shows that dysbiosis can lead to an overproduction of ghrelin, the “hunger hormone,” while simultaneously suppressing leptin and GLP-1. That’s a recipe for constant hunger and poor appetite control.

Let’s take an example: A person suffering from dysbiosis may finish a full meal and still feel ravenous 30 minutes later. This is not just a matter of willpower—it is a biological misfire caused by microbial imbalance.

Their gut is essentially sending mixed messages to the brain, whispering, “Keep eating,” even when fuel is no longer needed.

Even more troubling, some gut microbes thrive on sugar and refined carbs and can manipulate cravings to encourage the host—you—to consume more of what they need. Yes, your gut bacteria might be influencing your snack decisions.

In short, restoring gut balance isn’t just good for digestion; it is vital for regulating appetite and maintaining a healthy weight. Fix the gut, and the hunger cues may just start working in your favor again.

FAQs on Gut Dysbiosis and Obesity

Q-1: How can dysbiosis make the same meal yield more “usable” calories?

A-1: Certain microbial communities are unusually good at breaking down otherwise indigestible carbohydrates, producing extra short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) that the liver can turn into fuel or fat. If your microbiome leans toward these “super-extractors,” you may absorb a few dozen more calories per day from the same menu—small daily edges that compound over months.

Q-2: What is “metabolic endotoxemia,” and why does it matter for weight gain?

A-2: When the gut barrier is stressed, tiny fragments from bacteria can slip into the bloodstream and nudge the immune system into a low-grade, ongoing response. That background inflammation interferes with insulin’s signal, so more energy is shunted into storage. You might notice post-meal sleepiness, higher fasting triglycerides, or larger waist measurements despite modest changes in weight.

Q-3: How do bile acids connect dysbiosis to appetite and fat storage?

A-3: Gut microbes continually remodel bile acids, which act like hormones, talking to receptors that regulate blood sugar, appetite peptides, and heat production in tissues. A dysbiotic shift can tilt these signals toward lower satiety, less fat burning, and higher glucose output—quietly steering metabolism toward gain even without big changes in calories.

Q-4: Can missing microbes—rather than “bad” ones—push weight upward?

A-4: Yes. Some species help maintain the mucus layer, feed colon cells, and keep the barrier snug. When these guardians are scarce, the gut becomes leakier and less efficient at handling fats and sugars. People often report that high-fiber foods feel bloating or “don’t agree” with them—an indirect clue that helpful fermenters are underrepresented.

Q-5: If SCFAs are supposed to be beneficial, why do some people with obesity show higher SCFAs in stool?

A-5: Where and how SCFAs act matters. Stool levels reflect leftovers, not necessarily what’s absorbed or signaled to the brain and tissues. You can have high fecal SCFAs because the colon didn’t absorb them efficiently or because microbes produced them in proportions that don’t translate to appetite control and fat burning. Context—microbe mix, gut transit, and host response—determines whether SCFAs help or hinder energy balance.

How to nudge the system back: aim for 25–35 different plant foods weekly (count herbs, nuts, pulses), rotate fermented foods, time the last meal earlier in the evening, sleep on a steady schedule, and favor daily walking plus brief strength sessions. These habits restore barrier integrity, diversify microbes, and retune bile- and hormone-linked signals toward a more weight-friendly metabolism.

Examples from Daily Life: How Diet and Lifestyle Contribute to Gut Dysbiosis

In today’s fast-paced world, it is easy to develop unhealthy habits that contribute to gastrointestinal dysbiosis.

Let us look at a few examples from everyday life that can lead to an imbalance in gut bacteria and potentially cause weight gain:

- High-Sugar Diets: The consumption of sugary foods and drinks feeds harmful bacteria in the gut, promoting their overgrowth. When your diet is high in sugar, you create an environment in which bad bacteria thrive, contributing to oral dysbiosis and further disrupting the gut flora.

- Processed Foods: The frequent intake of processed foods, which often contain preservatives and additives, can also upset the balance of gut bacteria. These fast foods are laden with sugar and they provide little nutritional value for beneficial bacteria and encourage the growth of harmful strains, resulting in gi dysbiosis.

- Lack of Fiber: A diet low in fiber can lead to bowel dysbiosis. Fiber is essential for feeding the good bacteria in your gut and promoting the production of SCFAs. Without enough fiber, these beneficial bacteria begin to die off, allowing bad bacteria to flourish.

- Chronic Stress: The pressures of modern life often lead to high levels of stress, which can negatively affect your gut health. Stress hormones can disrupt the gut lining, leading to bacteria dysbiosis and increasing the risk of inflammation and weight gain.

- Antibiotic Use: While antibiotics are necessary for fighting infections, their overuse can wipe out not only harmful bacteria but also the beneficial bacteria in your gut. This imbalance can cause colonic dysbiosis, leading to long-term health effects, including obesity.

Takeaway

In conclusion, the design of your gut microbiome plays a far more significant role in your weight than you might think.

Gut dysbiosis—an imbalance of the bacteria in your digestive tract—can alter your metabolism, increase inflammation, and affect appetite regulation, all of which contribute to weight gain and obesity.

From influencing how your body stores fat to affecting the hormones that control hunger, gut flora dysbiosis has a profound impact on whether you can maintain a healthy weight.

While everyday factors such as diet, stress, and antibiotic use can lead to intestinal dysbiosis, the good news is that awareness of these triggers can help you make lifestyle changes to protect your gut health.

Although we did not dive into solutions in this article, it is clear that addressing gut health is key to tackling obesity from a holistic perspective.

In summary, gastrointestinal dysbiosis is more than just a gut issue—it is a weight issue.

By understanding the intricate connection between your gut microbiome and obesity, you can begin to appreciate the importance of maintaining a healthy balance of bacteria in your digestive system.

References: