When I first heard about Cushing’s syndrome, I had no idea what it meant, let alone its connection to weight gain.

After doing some research and talking to my doctor, I learned that Cushing’s syndrome involves an excess of the hormone cortisol, which leads to a host of physical changes, including obesity.

The condition sheds light on just how powerful hormones can be in regulating our body weight and overall health.

For people with Cushing’s syndrome, the effects of elevated cortisol levels are profound and often lead to a specific type of weight gain that is stubborn and difficult to manage.

This article by leanandfit.info delves into the relationship between cortisol and obesity, specifically within the context of Cushing’s syndrome.

I would explore how excess cortisol affects weight gain, why it leads to fat accumulation in particular areas of the body, and what mechanisms are at play.

By the end, you all would have a clear understanding of the pivotal role cortisol plays in obesity development in Cushing’s syndrome, as well as insights into how this information applies to everyday health management.

Contents of this Article:

- What is Cushing’s Syndrome?

- The Function of Cortisol in the Body

- Cortisol and Obesity: A Complex Relationship

- The Mechanism of Cortisol-Induced Weight Gain in Cushing’s Syndrome

- Truncal Obesity with Striae: The Signature Sign of Cushing’s Syndrome

- Real-Life Examples: How Cortisol Influences Daily Life and Weight

- FAQs on Cortisol in Cushing’s Syndrome and Obesity Development

- Conclusion: The Role of Cortisol in Cushing’s Syndrome and Obesity Development

What is Cushing’s Syndrome?

Cushing’s syndrome is like your body’s internal stress switch getting stuck in the “on” position. It happens when cortisol—the hormone responsible for your fight-or-flight response—stays elevated for too long.

Whether due to your body making too much cortisol (endogenous Cushing’s) or long-term use of corticosteroids (exogenous Cushing’s), the effects ripple across nearly every system in your body.

Let’s break it down point by point:

-

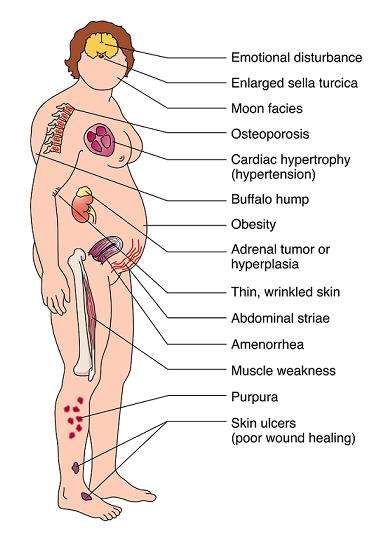

Weight Gain in Specific Areas:

This isn’t your usual weight gain. In Cushing’s syndrome, fat accumulates in distinct areas: the abdomen, face (“moon face”), and upper back (“buffalo hump”). According to research published in Endocrine Reviews, this is due to cortisol promoting fat storage around visceral organs, which is the most metabolically active and dangerous kind of fat. -

Muscle Weakness and Wasting:

Cortisol is not just storing fat—it’s breaking down muscle. High cortisol levels increase protein catabolism, leading to muscle wasting, particularly in the limbs. That’s why someone with Cushing’s may have thin arms and legs but a rounded torso. -

Skin Changes and Easy Bruising:

Cortisol thins the skin and weakens blood vessels. This leads to purple stretch marks (striae), fragile skin, and bruising with minimal trauma. It’s a telltale sign doctors look for. -

Emotional and Cognitive Effects:

High cortisol levels affect the brain too. Patients often report depression, anxiety, and difficulty concentrating. One study in The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism noted a significant link between hypercortisolism and hippocampal shrinkage—impacting memory and mood. -

Resistance to Weight Loss:

Unlike typical obesity, weight from Cushing’s syndrome is notoriously resistant to diet and exercise. This is because cortisol not only increases appetite but also slows metabolism and alters insulin sensitivity—making fat loss a metabolic uphill battle.

So if you’re dealing with unexplained weight gain and stubborn fat, it might not be your willpower—it could be your hormones staging a coup.

The Function of Cortisol in the Body

Cortisol is commonly known as the “stress hormone” because it is released by the adrenal glands in response to stress. However, its role in the body is far more complex.

Cortisol helps regulate metabolism, control blood sugar levels, and reduce inflammation. In short bursts, cortisol can be helpful—providing energy and improving focus.

But when cortisol levels remain elevated for too long, as in the case of Cushing’s syndrome, the effects can be harmful.

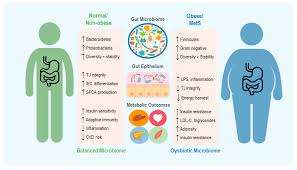

When cortisol is chronically elevated, it triggers a range of physiological responses that contribute to weight gain. It increases appetite, encourages fat storage (especially around the abdomen), and alters how the body metabolizes fats, proteins, and carbohydrates.

This relationship between cortisol and obesity is particularly evident in people with Cushing’s syndrome, who often experience rapid and significant weight gain.

Cortisol and Obesity: A Complex Relationship

The connection between cortisol and obesity is complex, but several key factors help explain why people with Cushing’s syndrome tend to gain weight.

First, cortisol increases appetite by stimulating the release of ghrelin, the “hunger hormone.” This leads to overeating, particularly cravings for sugary and high-fat foods.

Additionally, cortisol slows down metabolism, making it easier to gain weight even if calorie intake remains the same.

In people with Cushing’s syndrome, cortisol promotes the accumulation of visceral fat, which is the fat stored around internal organs.

This type of fat is more metabolically active and is linked to a higher risk of heart disease, type 2 diabetes, and other metabolic disorders.

A cortisol and weight gain study published in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism found that individuals with higher cortisol levels tend to have more visceral fat, emphasizing the strong link between stress hormones and obesity.

The Mechanism of Cortisol-Induced Weight Gain in Cushing’s Syndrome

To fully understand the role of cortisol in Cushing’s syndrome and obesity development, we need to look at the specific mechanisms at play.

Cortisol affects fat distribution by promoting fat storage in certain areas of the body, particularly the abdomen, face, and upper back.

This type of fat accumulation is referred to as truncal obesity with striae, a hallmark symptom of Cushing’s syndrome.

In addition to increasing fat storage, cortisol also breaks down muscle tissue to provide the body with energy.

This leads to muscle atrophy and reduced physical strength, further complicating efforts to lose weight. The cortisol and obesity mechanism highlights how the hormone disrupts the balance between muscle and fat, contributing to an unhealthy body composition.

Another significant factor is cortisol’s effect on insulin sensitivity.

Chronic exposure to high cortisol levels can lead to insulin resistance, a condition in which the body’s cells become less responsive to insulin.

Insulin resistance is a major driver of fat storage, particularly around the abdomen, and can eventually disturb your glucose metabolism.

People with Cushing’s syndrome often experience fat accumulation in areas like the face (commonly known as “moon face”) and upper back (resulting in a “buffalo hump”).

This unique pattern of fat distribution is directly linked to the influence of cortisol on fat cells.

Truncal Obesity with Striae: The Signature Sign of Cushing’s Syndrome

One of the most recognizable signs of Cushing’s syndrome is truncal obesity with striae, where the body gains fat predominantly around the abdomen and torso.

This is not the typical kind of weight gain most people experience. Instead, it is accompanied by purple or red stretch marks (striae) on the skin, which result from the rapid expansion of fat in these areas.

The presence of truncal obesity is a key indicator of Cushing’s syndrome, differentiating it from other forms of obesity. These striae occur because cortisol weakens the skin’s collagen structure, making it less elastic and more prone to tearing as fat accumulates.

I have met people struggling with Cushing’s syndrome who were frustrated by their inability to lose weight, especially from their midsection, despite trying various diets and exercise routines.

Their experience of weight gain was unique because of how cortisol specifically targeted certain areas of their body for fat storage.

Understanding this cortisol and obesity mechanism helped them realize that the issue wasn’t just about calories in and calories out—it was about how their hormones were affecting fat distribution.

FAQs on Cortisol in Cushing’s Syndrome and Obesity Development

Q-1: Why does Cushing’s syndrome drive a “belly-first” obesity pattern?

A-1: Chronic cortisol excess shifts fat storage toward the abdomen and trunk while thinning limbs. Cortisol boosts liver glucose production, alters how fat cells mature, and encourages lipid deposition in visceral depots. Those depots also regenerate more active cortisol locally, amplifying central fat gain alongside insulin resistance and an atherogenic lipid profile.

Q-2: If my blood cortisol isn’t sky-high, can cortisol still be part of my obesity?

A-2: Yes. Tissue-level cortisol can be high even when blood tests look “normal.” Enzymes in fat and liver cells can convert inactive cortisone into active cortisol, creating a local surplus that promotes fat storage and metabolic dysfunction. This helps explain why some people show a Cushing-like fat distribution without overt hypercortisolism on standard labs.

Q-3: How does cortisol change appetite and daily energy regulation?

A-3: Cortisol influences hunger circuits and food reward. When elevated—especially with poor sleep or late eating—it can increase drive for energy-dense foods, heighten evening appetite, and blunt diet-induced thermogenesis. At the same time, it may reduce spontaneous daily movement. The combination of higher intake and slightly lower “burn” favors gradual, central weight gain.

Q-4: How do clinicians distinguish true Cushing’s from “pseudo-Cushing” states in obesity, depression, or heavy alcohol use?

A-4: After ruling out steroid medications, clinicians use screening tests that probe cortisol rhythms and feedback control: late-night salivary cortisol, an overnight dexamethasone suppression test, or 24-hour urine free cortisol. Because several conditions can partially mimic Cushing’s, results are interpreted with repeat measurements, proper timing, and the clinical picture (signs like easy bruising, proximal muscle weakness, purple striae, refractory hypertension).

Q-5: If excess cortisol is the driver, what improves when it’s treated?

A-5: Lowering cortisol—by removing an ACTH- or cortisol-secreting tumor or using targeted medications—typically reduces central adiposity, improves blood pressure, lowers fasting glucose and A1C, and normalizes lipids. Even partial control can ease insulin resistance and restore a healthier day–night cortisol pattern.

After remission, the biggest sustainers are consistent sleep/wake anchors, a protein-forward diet that limits late-night calories, regular aerobic activity plus resistance training for muscle recovery, and periodic follow-up to catch recurrence early.

Takeaway: Cortisol does not just track with stress—it actively redirects where and how the body stores energy. In Cushing’s, that redirection becomes extreme; in common obesity, milder rhythm disruptions and local tissue activation can still tilt the scale toward central fat.

Real-Life Examples: How Cortisol Influences Daily Life and Weight?

Living with elevated cortisol levels changes the way you feel about food, exercise, and even sleep.

I remember going through a particularly stressful period in my life and noticing how my appetite shifted. I craved comfort foods—high in sugar and fat—and felt too exhausted to exercise.

I could not help but wonder, can cortisol cause this kind of weight gain?

It turns out that even in people without Cushing’s syndrome, chronic stress can lead to elevated cortisol levels and, consequently, weight gain.

For those with Cushing’s syndrome, the effect is amplified. Simple daily activities like walking or lifting light objects can become tiring due to muscle loss, making it harder to stay active.

The combination of muscle weakness, insulin resistance, and fat accumulation creates a cycle that’s difficult to break.

This is why understanding the role of cortisol is crucial for anyone trying to manage weight gain in Cushing’s syndrome or even stress-induced obesity.

Takeaway

In conclusion, cortisol plays a central role in the development of obesity in Cushing’s syndrome.

Elevated cortisol levels lead to increased fat storage, particularly in the abdominal area, as well as muscle loss and insulin resistance.

This combination of factors creates a unique pattern of weight gain that is difficult to manage without addressing the underlying hormonal imbalance.

The relationship between cortisol levels and obesity is clear, and understanding how this hormone functions within the body can help those affected by Cushing’s syndrome find more effective ways to manage their weight.

While the condition requires medical intervention, lifestyle changes that reduce cortisol levels, such as stress management, regular physical activity, and a balanced diet, can help alleviate some of the weight-related symptoms.

If you have been struggling with unexplained weight gain and suspect that cortisol might be involved, I encourage you to speak with a healthcare professional.

Managing cortisol levels may be the key to unlocking a healthier, more balanced approach to weight management.

References: